Typography | Task 1 : Exercises

23/8/21 - 27/9/21 (Week 1 - Week 6)

Jane Chong Yun Ann (0344255)

Typography / Free Elective in Bachelor of Design in Creative Media

Task 1: Exercises

Task 1: Exercises

LECTURE NOTES

Lecture 1 Week 1 | Development

In the first lecture class, Mr Vinod and Dr Charles briefed us on our

module and gave instructions on how to create our own blog/ e-portfolio.

He provided many references on how we can write our own reflections as

well as provided seniors' e-portfolios as samples for us to refer to. They

also provided a lecture playlist so that we are able to listen and learn

each topic at our own pace.

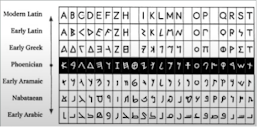

The first recorded topic was on the history of typography. From the

Western perspective, early forms of writing were in the form of carving or

scratching. As the tools used were simple, the letterforms consisted of

simple straight lines and pieces of circles and were read from right to

left.

Figure 1.1: Evolution from the Phoenician alphabet, Week 1

(27/8/21)

The Greeks changed the direction of writing from right to left, to left to

right. They called this style 'boustrophedon', which means 'how the ox

plows'. This also meant that the orientation of letterforms changed

directions according to how it was read.

Figure 1.2: How 'boustrophedon' looks like, Week 1 (27/8/21)

Carvers used to paint on the marble before carving the letters. Based on the

brushstrokes, there were certain weights and strokes that carried to the

carved letterforms. This is later formed into the serifs we see today.

Figure 1.3: Phoenician to Greek to Roman letterform, Week 1

(27/8/21)

Figure 1.4: Square capitals, Week 1 (27/8/21) Figure 1.5: Rustic capitals, Week 1

(27/8/21)

Square capitals were letterforms in the 3rd - 10th-century C.E. These were

letterforms that had serifs at the end of the main strokes of approximately

60 degrees off the perpendicular using a reed pen. There were also rustic

capitals, which was a compressed version of square capitals. While twice the

number of words can be included and it took up lesser time, it was harder to

read. It was interesting to note that both square and rustic capitals were

usually only used in documents of some intended performance. Daily

transactions usually made use of cursive handwriting that was simplified for

speed, giving birth to lower case letterforms.

Uncials contained some aspects of Roman cursive hand and, at small sizes,

were more readable than rustic capitals. Half-uncials were then developed

as a formal beginning of lowercase letterforms.

Figure 1.6: Half-uncials, Week 1 (27/8/21)

Charlemagne then entrusted Alcuin of York, Abbot of St Martin of Tours to

standardize all ecclesiastical texts. This standard of text was set for a

century. As Charlemagne's empire dissolved, regional variations on Alcuin's

script arose. A letterform known as Blackletter (textura) became popular in

northern Europe, featuring a condensed and strongly vertical letterform. In

the north, a rounder and more open hand letterform known as rotunda gained

popularity.

Figure 1.7: Blackletter (textura), Week 1 (27/8/21)

Gutenberg used his engineering, chemistry, and metalsmithing skills to

create a machine that could print scribes' writings at a much quicker pace

compared to humans' writing. Hence, greater number of books could be written

in a shorter span of time.

Text type classifications:

- 1450 Blackletter - Based on the hand-copying styles used for books in northern Europe.

- 1475 Oldstyle - Based on lowercase forms by Italian humanist scholars for book copying and uppercase forms found in Roman ruins.

- 1500 Italics - Based on contemporary Italian handwriting, cast to complement roman forms.

- 1550 Script - Attempt to replicate engraved calligraphic forms; ideal for shorter applications.

- 1750 Transitional - Refinement of oldstyle forms; thin to thick relationships were exaggerated.

- 1775 Modern - Further rationalization of oldstyle forms, added contrast between thick and thin strokes, serifs.

- 1825 Square / Slab Serif - Little variation between thick and thin strokes, developed to needs for heavy type commercial printing.

- 1900 Sans Serifs - Eliminated serifs altogether.

- 1990 Serif / Sans Serifs - Typefaces that include both serif and sans serif alphabets (and stages between the two).

Additional:

- 'Kernel' - Reducing space between letters.

- 'Letter spacing' - Increasing space between letters.

Questions:

1) Since the Phoenicians initially read words from right to

left, and the Greeks developed the 'boustrophedon' style (start left to

right, and then right to left..), who finalized it to read words ONLY from

left to right?

Lecture 2 Week 2 | Basic

Typeface - Refers to the family of fonts (eg: Futura).

Fonts - The specific weight (eg: Futura Condensed).

In this recorded lecturer, we covered the basic terminologies in

typography.

Baseline: The line at the visual base of the letterforms.

Median: The line defining the x-height of letterforms.

X-height: The height of lowercase 'x' in any typeface.

-

Arm: Short strokes off the stem of the letterform (can be

horizontal or inclined upwards).

Ascender: The portion of the stem of a lowercase letterform that

projects above the median.

Barb: The half-serif finish on some curved stroke.

Beak: The half-serif finish on some horizontal arms.

Bowl: The rounded form that describes a counter. It can be

open or closed.

Bracket: The transition between serif and the stem.

Cross-bar: The horizontal stroke in a letterform that joins

two stems together.

Cross stroke: The horizontal stroke that connects.

Crotch: The interior space where two strokes meet.

Descender: The portion of the stem of a lowercase

letterform that projects below the baseline.

Ear: The stroke extending from the main

stem or body.

Em/en: Refers to the width of an uppercase 'M'. An en is half the

size of an em.

Finial: The rounded non-serif terminal to a

stroke.

Leg: The short stroke off the stem, wither at the bottom or inclined

downward.

Ligature: The character formed by combination of two or more

letterforms.

Link: The stroke that connects the bowl and

the loop of a lowercase 'g'.

Loop: In some typefaces, it is the bowl created in the descender of

the lowercase 'g'.

Shoulder: The curved stroke that is not part of a

bowl.

Spine: The curved stem of the 'S'.

Spur: The extension the articulates the junction between the curved

and rectilinear stroke.

Stress: The orientation of the letterform, indicated by the thin

stroke in the round forms.

Stroke: Any line that defines the basic letterform.

Swash: The flourish that extends the stroke of a letterform.

Terminal: The self-contained finish of a stroke without a serif. It

can be flat, flared, acute, grave, concave, convex or rounded (like finial).

-

Uppercase: Capital letters, including certain accented vowels.

Lowercase: Has the same letters as uppercase letters.

Small Capitals: Uppercase letterforms that draw to the x-height of a

typeface. Mostly found in serif fonts as part of what is called as an

'expert set'. It is important to not confuse real small caps with those that

are artificially generated.

Figure 2.1: Small capitals, Week 2 (1/9/21)

Uppercase Numerals: Also known as lining figures, with the same

height as uppercase letters and are all set to the same kerning width. Most

successfully used with tables.

Lowercase Numerals: The numbers are set to x-height with ascenders

and descenders. Best used when upper and lowercase letterforms are used.

They are less common in sans serif typefaces.

Figure 2.2: Uppercase numerals (top) and lowercase numerals (bottom),

Week 2 (1/9/21)

Additionally, we learnt about how it is important to be acquainted with all

the characters (including punctuation and miscellaneous characters)

available in a typeface before choosing an appropriate typeface for the job.

Ornaments: Used as flourishes in certificates or invitations. These

are usually provided as a font in a larger typeface family. Only a few

typefaces contain ornamental fonts as part of the entire typeface family

(eg: Adobe Caslon Pro).

Figure 2.3: Ornaments, Week 2 (1/9/21)

Describing Typefaces

- Italics: Refers back to the 15th century Italian cursive handwriting.

- Most fonts have a matching italic version. Small capitals, however, are almost always only roman.

- Oblique: They are typically based on roman typefaces.

- Roman: Uppercase forms derived from inscriptions of Roman monuments. A slightly lighter stroke in roman is known as 'Book'.

- Boldface: Has thicker stroke than a roman form, also known as 'semibold' , 'medium', 'black', 'extra bold' or 'poster' (in some typefaces).

- Light: Lighter stroke than the roman form. 'Thin' refers to even lighter strokes.

- Condense: A compressed version of the roman form. 'Compressed' refers to extremely condensed styles.

- Extended: An extended variation of a roman form.

Figure 2.4: Different categories of typefaces, Week 2 (1/9/21)

The 10 typefaces represents 500 years of type design, where they achieved

the goal of easy readability and appropriate expression of contemporary

aesthetics. It is important to study on how to use these 10 typefaces

carefully and effectively.

Figure 2.5: 10 typefaces, Week 2 (1/9/21)

These typefaces are all unique in terms of x-height, line weight, relative

stroke widths and in the feelings they evoke.

Lecture 3 | Text I

Kerning: The automatic adjustment of space between the letters.

Letterspacing: Adding space between the letters.

The addition and removal of space in a word or sentence is known as

'tracking'. Mr Vinod then showed a demo on how to apply tracking using Adobe

InDesign.

When dealing with words that has all capital letters, kerning is essential

to reduce the awkward and irregular spacing in between the letters. As more

tracking is applied, the readability of the word reduces.

Letterspacing uppercase letters are common, but lowercase letters

within text is discouraged. This is because uppercase

letterforms are meant to be able to stand on their own, while lowercase

letterforms need the counterform created between the letters to maintain the

line of reading.

Figure 3.1: How kerning affects readability of bodies of text, normal

tracking (top left), loose tracking (top right), tight tracing (bottom),

Week 3 (7/9/21)

The most natural way to format text is flush left, as it mimics the

asymmetrical experience of normal handwriting. Each line starts at the

same point but ends wherever the last word on the line ends. There is also

equal spacing in between the words.

Centered format imposes symmetry upon the text. There is equal

value and weight at both ends of any line, adding pictorial quality to an

otherwise non-pictorial material. It is important to amend line breaks so

that the text does not appear too jagged.

Flush right places emphasis on the end of the line. This is useful in situations where the relationship between the text and image may be vague without a strong orientation to the right (eg: captions).

Justified is another format that impose a symmetrical shape.

This is achieved by expanding or reducing spaces in between words, and

sometimes, letters. This can result in 'rivers' of white spaces running

vertically through the text, hence, it is important to pay attention to the

linebreaks and add hyphenation wherever needed.

A typographer's first job: Clearly and appropriately present the author's

message. If the type is seen before the words, change the type. Different

typefaces better convey different type of messages, hence, it is important

to know which typeface best suits the message at hand.

Additionally, sensitivity to the differences in textures and colours of the

typefaces is essential to create successful typographies. To determine if a

text is readable, the x-height is compared to the descender (the space below

the x-height) and the ascender (the space above the x-height). If the

x-height is larger than both, the text is considered as readable.

Figure 3.2: Different typefaces in bodies of text, Week 3 (7/9/21)

An example of how 'colour' plays a part in the readability of text.

Typefaces such as Jenson Garamond have thicker strokes, hence, appearing

'darker' and the greater contrast makes the body of text more readable than

other 'lighter' fonts such as Bodori and Bembo.

The goal in setting an appropriate text type is to allow for easy, prolonged

reading.

Type size: Text type should be large enough to be read easily at an

arms length.

Leading: Otherwise known as the distance between the baselines of two

different lines of texts. If the leading is too little, it can encourage

vertical eye movement, causing the reader to loose their line of

reading easily. On the other hand, if the type is set too loosely it can

create distracting striped patterns.

Line length: A good rule of thumb is to keep line length between

55-65 characters as extremely long or short line lengths can affect reading.

It is also important to express hierarchy in texts through subheadings.

Cross aligning headlines and captions reinforces the architectural

sense of the page while articulating complimentary vertical rhythms. This

can be achieved by ensuring the size of leading of each body of text can be

factors of each other. In Figure 3.3, the caption is leaded at 9pts while

the regular text type is leaded to 13.5 pts.

Figure 3.3: Good cross-alignment, Week 3 (7/9/21)

Lecture 4 | Text II

There are several ways to indicate paragraphs.

- A 'pilcrow' symbol was used to indicate paragraph spacing in medieval manuscripts (though seldom used today). This is shown in Figure 4.1.

- There is a line space (leading) between paragraphs. If the line space is 12pt, the paragraph is 12pt. This is to ensure cross-alignment across columns of text.

- Standard indentation. The indent is the same size as the line spacing or the point size of the text. Indentation is best used when the text is in a justified format.

- Extended paragraphs; creates unusually wide columns of text. It is sometimes used in academia writings. This is shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.1: Pilcrow symbol, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Figure 4.2: Leading and line spacing, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Figure 4.3: Extended paragraph, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Widows and orphans must be avoided at all costs in design.

Widow: A short line of type left alone at the end of a column of

text.

Orphan: A short line of type left alone at the start of a new column.

Figure 4.4: Widow and orphan, Week 4 (14/9/21)

In justified formats, widows and orphans are considered as serious gaffes.

Flush right and ragged left texts may be more forgiving to widows, but

orphans cannot be excused. A solution to widows is to rebreak the line

endings throughout the paragraph. For orphans, it requires more care.

In large amounts of texts, important parts of the text can be highlighted.

There are different ways to highlight for emphasis:

- Italics (same typeface)

- Bold (same typeface)

- Changing the typeface and making it bold

- Changing the colour of the important text

- Placing a body of colour behind the text

- Quotation marks (not 'prime'! refer Fig 4.8)

For the third method, the new typeface may look larger. Sans serif fonts

tend to look 'larger' than serif typefaces. Hence, the point size of the

new text may need to be changed to make it look similar in size (ref Fig

4.5). This is also applicable for numerals that appear 'larger' than their

alphabet counterparts (ref Fig 4.6).

Figure 4.5: Adjusting point size, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Figure 4.6: Adjusting point size, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Sometimes it is necessary to place certain typographic elements outside the

left margin of the column. This is to maintain a strong reading axis.

Figure 4.7: Elements outside the left margin, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Figure 4.8: Prime and quotation marks, Week 4 (14/9/21)

It is important to differentiate the prime symbol (used to represent feet

and inches) from quotation marks (which are slanted).

Creating a typographic hierarchy is important to signify to the reader the

relative importance and relationship between the text.

A head: Indicates a clear break between the topics within a

section.

Figure 4.9: A head, Week 4 (14/9/21)

B head: Indicates a new supporting argument or example for the topic.

It does not interrupt the text as strongly as A heads do.

Figure 4.10: B head, Week 4 (14/9/21)

C head: Although not common, it highlights

specific facets of material within B head text. There is usually an em space

between the C head and the new paragraph text.

Figure 4.11: C head, Week 4 (14/9/21)

Lecture 5 | Understanding

Some uppercase letterforms (such as below) suggest symmetry, but it is in

fact, not symmetrical. The Baskerville stroke forms have different weights.

The width of the left stroke and right stroke is different, showing the type

designer's care to create both harmonious and expressive letterforms.

Figure 5.1: Asymmetrical uppercase letterforms, Baskerville (left),

Univers (right), Week 5 (21/9/21)

The differences and complexity of each individual letterform can be seen

when we compare the two lowercase 'a' of seemingly similar sans-serif

typefaces, Helvetica and Univers.

Figure 5.2: Differences between Helvetica (left) and Univers (right),

Week 5 (21/9/21)

When maintaining x-height, it is important that curved strokes (such as 'a'

and the curved stroke in 'r') must rise above the median, or sink below the

baseline to appear to be the same size as the vertical and horizontal

counterpart strokes.

Figure 5.3: Maintaining x-height with curved strokes, Week 5

(21/9/21)

It is also important to be sensitive to the counter form; the space that is

contained by the strokes of the letterforms. The counter affects the

readability of the sentence.

Figure 5.4: Counter form, Week 5 (21/9/21)

Contrast is also apparent in typefaces. This can be small+organic,

large+machined, small+dark, large+light..etc. To understand different

information, there needs to be different contrast.

Figure 5.5: Contrast in typefaces, Week 5 (21/9/21)

INSTRUCTIONS

<iframe

src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/17Pcc6te7YofVyQeTHGc726eL8o3sJSHD/preview"

width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

EXERCISES

Task 1: Exercises - Type Expression

We were given words to choose and create a type expression for each word.

The words I chose were 'terror', 'error', 'melt', and 'gone'. At least three

different sketches needed to be done for each word. I sketched out my ideas

in Medibang Paint Pro as I did not have access to the Adobe license yet. We

also were only allowed to use black and white as well as the 10 typefaces

provided.

Figure 7.1: Sketches of the type expression, Week 2 (30/8/21)

My personal favourite is the last sketch for 'melt' and 'gone'. I tried to

sketch the font as close as possible to how the font will look like to get

the best visualization for each type of expression.

After obtaining feedback, I proceeded to digitize the type expressions in

Adobe Illustrator.

Figure 7.2: Digitization of 'melt', Week 2 (5/9/21)

I digitized two of my favourite 'melt' sketches. It was a new experience

to use the pen tool to draw the droplets, the cone and the puddle, pretty

satisfying too. I decided to keep the left digitization as I felt that the

cone concept was pretty unique :D.

Figure 7.3: Digitization of 'terror', Week 2 (5/9/21)

For the word 'terror' I attempted two of the sketches suggested by Mr Vinod.

I made use of the warp tool as I felt it added an extra sense of unease and

imbalance, almost suggesting that the word is 'shaking with terror'.

In the right digitization, I changed the perspective from the original

sketch as I felt it had a stronger effect when it looms forward instead. I

also added a gradient to the background and shadow to increase the looming

effect. In the end, I kept the left one as I felt that the stark contrast

between the black background and white words invokes a greater sense of

terror.

Figure 7.4: Digitization of 'gone', Week 2 (5/9/21)

I attempted four different fonts for the word 'gone'. With peer feedback

stating that the words were a little small, I enlarged it as well. While I

liked the storybook-like effect of the serif fonts, I felt that they were

more noticeable in general. Thus, I finalised Futura Std (Light Condensed)

as it took up the least space. Another more subtle change was the

different font size of the letter 'e', which makes it less noticeable.

FINAL DIGITIZATION:

Figure 7.5: Digitization of type expressions, Week 2 (5/9/21)

'Error' only had one attempt as it was clear that it expressed the meaning

of the word the best. I adjusted the kerning in 'gone' to better express

the type expression as well.

Figure 7.6: Final Type Expression (JPG), Week 3 (8/9/21)

Figure 7.7: Final Type Expression (PDF), Week 3 (8/9/21)

Figure 7.8: Rule of Thirds with 'melt', Week 3 (8/9/21)

We were then instructed to choose one of the type expressions to animate (in

terms of expressing its meaning). I chose 'melt' as I felt it was the most

unique and strong concept I had come up with.

Figure 7.9: First gif of 'melt', Week 3 (9/9/21)

I was just okay with it, it was not bad, but I was not satisfied. And I had

itchy hands, so I continued with the flow of this animation to let the

letters 'm' and 't' plop to the bottom.

Figure 7.10: Second gif of 'melt', Week 3 (9/9/21)

After uploading it to Facebook, Mr Vinod gave feedback to pause the loop at

the last frame for 3/5 seconds. I added an additional two frames to not make

the gif end so abruptly.

Figure 7.11: Final Type Expression Animation (GIF), Week 3

(9/9/21)

Task 1: Exercises - Text Formatting

This exercise was broken down into two main parts:

- Write our name in all of the 10 different typefaces, and apply kerning, tracking to it as appropriate

- Arrange the given body of text while also applying kerning, tracking, leading and cross-alignment

Personal favourites:

-Serifa Std, where I italicise all letters except the vowels as it gave an

interesting effect, almost emphasizing the pronunciation.

-Futura Std Light, very futuristic and minimalistic.

I remember at one point in doing this exercise, my own name started looking

weird to me.

Next came the actual text formatting task - format a body of text with its

header, sub-header, body and caption. The things to look out for:

- Font size (8-12pt)

- Line Length (55-65/50-60 characters)

- Text Leading (2/2.5/3 pts larger than font size)

- Ragging (Left alignment) / Rivers (Justification)

- Cross alignment

- No Widows or Orphans (don't take this out of context please)

Figure 8.2: Text Formatting attempts, Week 4 (18/9/21)

Honestly, I was a little stumped when I first started. I followed Mr Vinod's

tutorial video and thought "hey, it already looks good, what more is there

to do?". But I know better than to follow that train of thought.

I made several attempts, each with different plays on the title, sub-title,

images, number of columns etc. In general, I used a font size of 9pt with a

leading of 12pt. I also added kerning, tracking and force line break

wherever applicable. I found the last two text formatting the most

interesting.

Figure 8.3: Cross-alignment in text formatting, Week 4 (18/9/21)

Following Mr Vinod's feedback, I decided to change the format of the text

to left alignment instead of left justification to prevent the rivers from

forming. As usual, I added kerning and tracking wherever possible to

reduce the ragging on the right of the text.

Figure 8.6: Final text formatting (PDF), Week 4(20/9/21)

Time Allocation

Type Expression

Sketch: ~2 hours

Digitize: ~3-4 hours

Animate: ~2 hours

Text Formatting

Arranging: ~3-4 hours

Blogging: ~1 hour

Total: ~11-13 hours

FEEDBACK

WEEK 2

General Feedback from Dr Charles:

Severe distortion issues.

Specific Feedback from Mr Vinod:

ERROR - The third row has good execution, can attempt to pursue that.

MELT - The first row is acceptable for distortion, but the fourth row

is stronger so that can be pursued.

TERROR - The looming shadow in the second and the fourth row are

good. The

GONE - The first is good, the fade in the third row is good. The

second row can be pursued as there are no graphical elements.

Student Feedback:

ERROR - The second row design looks good.

MELT - The first row has a nice 3D effect.

TERROR - The third row has a creepy effect.

GONE - The second and third row looks good, the size of the word may

be too small.

Week 3

General Feedback:

We should make better use of the spaces in the square container.

Specific Feedback:

MELT - Can be moved a little higher or made a little bigger to

reduce the empty space above (but not equal to the bottom negative space due

to the difference in surface area). It is possible to tilt it slightly to

increase dynamism.

TERROR - The 'O R' can be made smaller and moved to the top right,

and the 'T E R R' can be made bigger so that the container vertical ratio is

around 70/30, to increase the sense of terror.

MELT Animation - Pause the loop at the last frame.

Week 4

General Feedback:

The general format and content of our blog should follow a standard.

Specific Feedback:

Good work on the static animation and animation, but ensure that the final

submission contains an embedded PDF, PNG and GIF. Mr Vinod also commended on

the details I included in the blog.

Week 5

Specific Feedback:

Task 1 Ex 2: Rivers were too evident in the body text and pull-quote. The

PDF submission has two artworks, you are only supposed to submit one — the

final. Need more practice overall decent.

REFLECTION

EXPERIENCE

I have never really experimented with typography, so this was something

rather new. It was interesting to find ways to play around with the words to

express their meaning. While it was challenging to limit it to the 10

typefaces, it was a fun limitation. As of now, the basic/main functions of

Adobe Illustrator plays a huge part in these exercises.

For the text formatting exercise, I first started out very safe: title on

the top left, sub-heading below, everything aligned, neat and compact. I

think as I started getting more used to the functions of InDesign, I had

more courage to try out different alignments. The process of kerning and

tracking took quite some time to get used to; it gets annoying when a river

forms after kerning, or when an orphan / widow pop up after tracking.

OBSERVATION

'Terror' was a terror to face as I could not come up with any

unique ideas. I also realized other students had similar ideas for 'melt'

too as well as had more interesting ideas for 'gone'. I found by making the

initial sketch as close to the original font as possible, it was much easier

to arrange the actual type expression and it reduced the time needed to go

through suitable fonts and I can spend more time experimenting with

different designs.

FINDINGS

I learned that different typefaces can carry a certain weight, which can

convey a different message. Adobe Illustrator is a very,

very powerful software, and its smart guides help you place different

elements aligned with other elements. It is almost scary to think someone

actually thought and developed this application. The little history behind

the typefaces gave me a glimpse of what typography used to look like before

and how it developed. While it is not very well-known, learning the

'behind-the-scenes' of these typefaces made me appreciate how readable and

well-thought the fonts are made to be, a little more (and I feel myself

subconsciously starting to judge every text medium I see oh no).

I just found out that the uppercase of the letter 'A' in Univers is not

symmetrical, my whole life is a lie.

FURTHER READING

From the book list that were recommended, I chose "Typographic design: Form

and Communication" by Rob Carter, Philip B. Meggs, Ben Day, Sandra Maxa and

Mark Sanders.

Reference: Carter, B., Day, B., Meggs, P. B., Maxa, S., & Sanders, M.,

(2015). Typographic design: Form and Communication. Hoboken, New Jersey:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 13.1: Book cover of Typographic design: Form and Communication,

Week 2 (1/9/21)

I read more on the historical classification of typefaces. The book showed

typefaces that were not presented in Mr Vinod's recorded lecture.

Digital typography has made a vast variety of typefaces easily accessible.

Many efforts have been made to categorize the typefaces. Different styles

add different variations and serves a different purpose. For sans serifs, I

learned that the stress is almost always vertical and many of the sans

serifs typefaces are geometric in shape while some combine organic and

geometric aspects into the typefaces.

The main aim of a letterform is to convey a distinctive message to the mind,

hence, it must be designed with clear contrast for the reader to be able to

decipher it without trouble. Hence, legibility of a typeface is important in

deciding which typefaces are suitable for different scenarios. It is

important that each of the 26 letters of the alphabet are distinguishable

from each other in the typeface. In general, letters can be clustered into

four groups of their contrasting properties:

- Vertical

- Curved

- Combination of vertical and curved

- Oblique

Letters from the same groups are more likely to be confused, hence, letters

within a word are most legible when an equal number of letters from each

group are taken.

Figure 13.3: The four groupings of letter, vertical, curved, combination,

oblique (top to bottom), Week 3 (7/9/21)

Interestingly, the upper halves and the right halves of the letters are more

recognizable than their counterparts. This can be observed in Figure 13.4 and

Figure 13.5.

Figure 13.4: Division of letters into upper and lower halves, Week 3

(7/9/21)

Figure 13.5: Division of letters into right and left halves, Week 3

(7/9/21)

There are, however, exceptions where some letters are more distinguishable

with their left halves, such as the letters 'b' and 'p'.

Comments